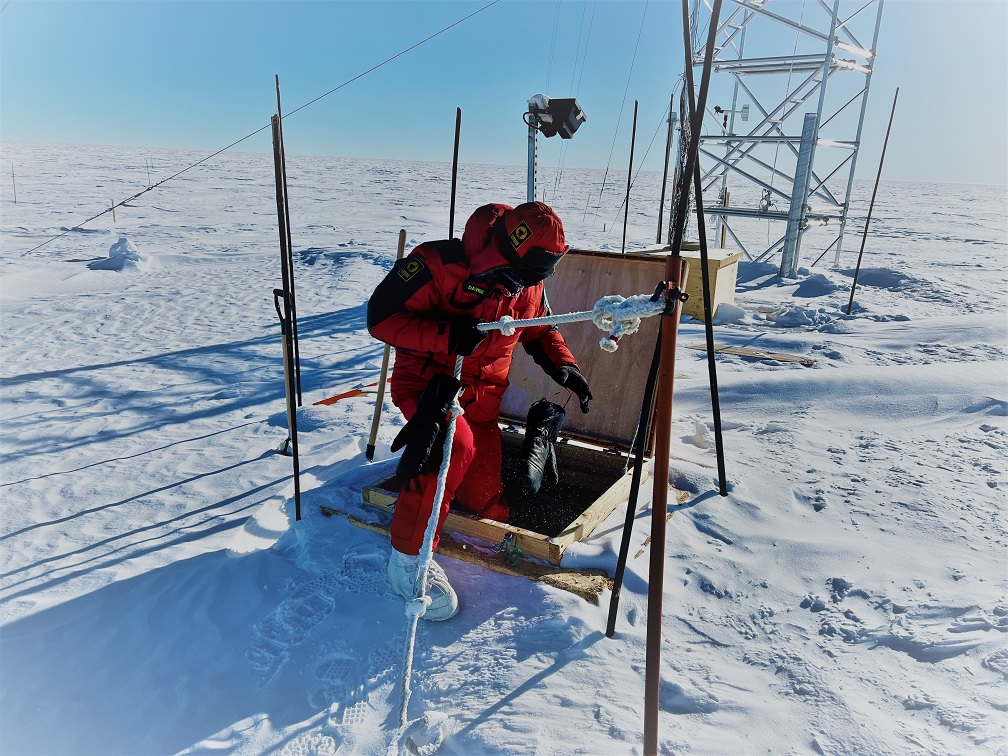

Over the past two weeks, Claude, our mechanic, has devoted most of his days to end-of-winter snow clearance operations.

In particular, he has been removing the snow that the wind has built up in the two pits that form the access ramps to our cellars.

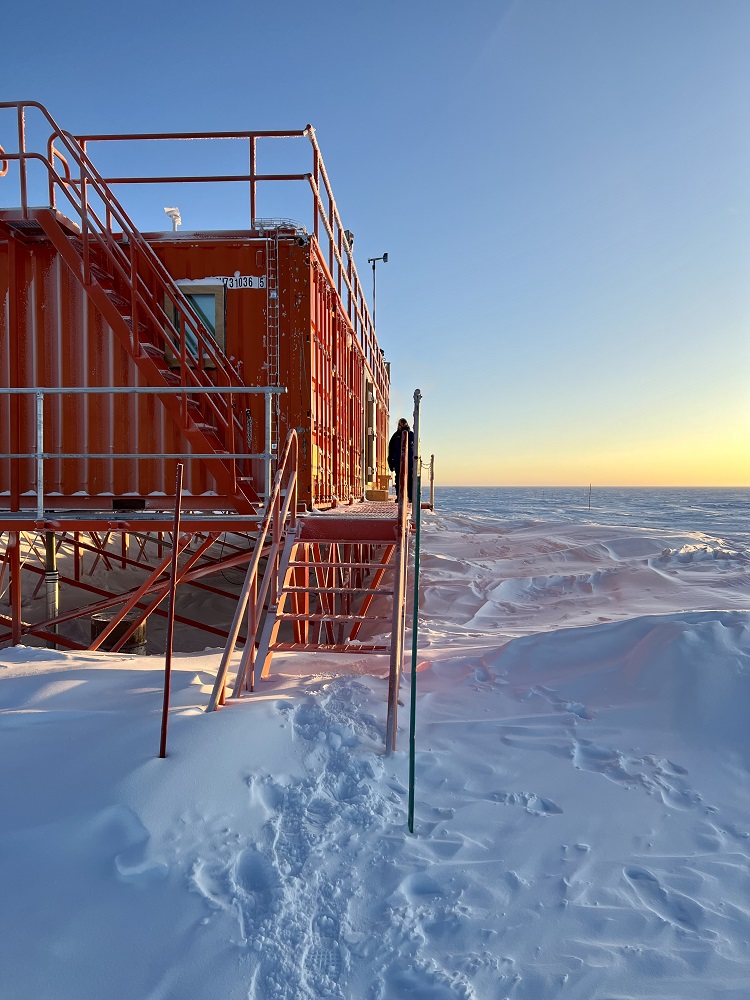

On Sunday, after a *rather* heavy lunch, we went for a walk with Claude and Jacopo to see the results of his work and discover these places that I didn’t know yet.

We started with the ‘balloon cave’. This cave takes its name from its special construction technique, imported from Scandinavia: a pit is dug, a gigantic balloon is inflated, snow is put back on top, little by little, allowing it to settle and, after a few weeks, the balloon is removed. All that’s left to do is close the entrance and we’ve got our cellar!

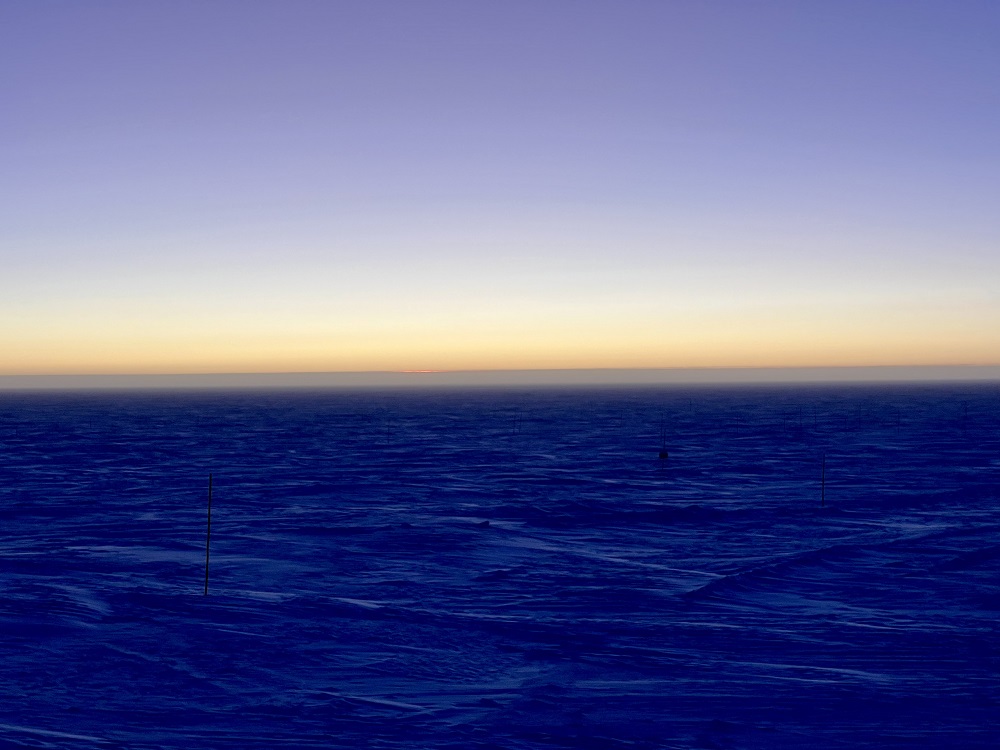

This is used to put our vehicles into winter storage, protecting them from the wind and snow and limiting their exposure to the cold (apart from the surface layer, the ice on which our station sits has a constant temperature corresponding to the average annual temperature of -51°C).

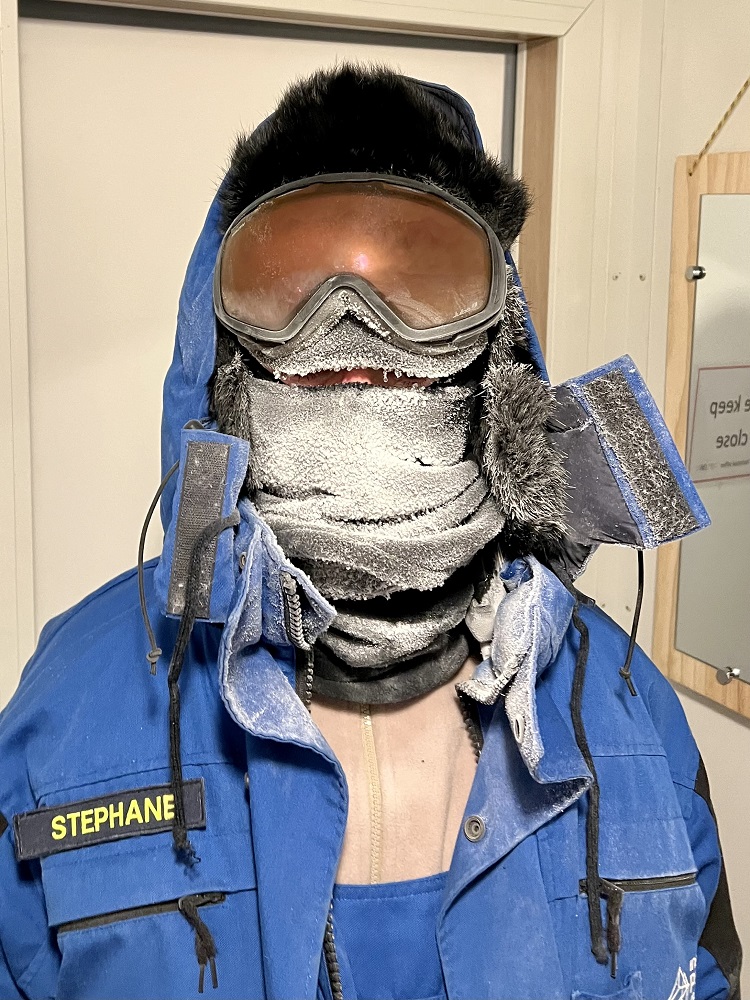

In fact, all these vehicles are unusable below -45°C because the plastics would break and the fuels would become pasty. Only our robust, old-fashioned, all-metal ‘loader’ works in winter (and even then, it has to be stored and started ‘warm’, i.e. at -30°C).

When you see this photo, you may realise the work Claude has done: the accumulated snow (although not packed down) reached the surface, some ten metres above our feet!

Leaving the balloon cave, we walked a kilometre through the summer camp to reach the second cave.

The technology here is a little different, as the walls are made of metal. This is the ‘Turbosider’ cave, named after the company that makes the structure.

Here you can see the ice crystals growing on the walls, giving the place a fairytale-like appearance.

While the contents of the first part of Turbosider resemble those of the balloon cave (vehicles in winter storage), at the back there’s a door.

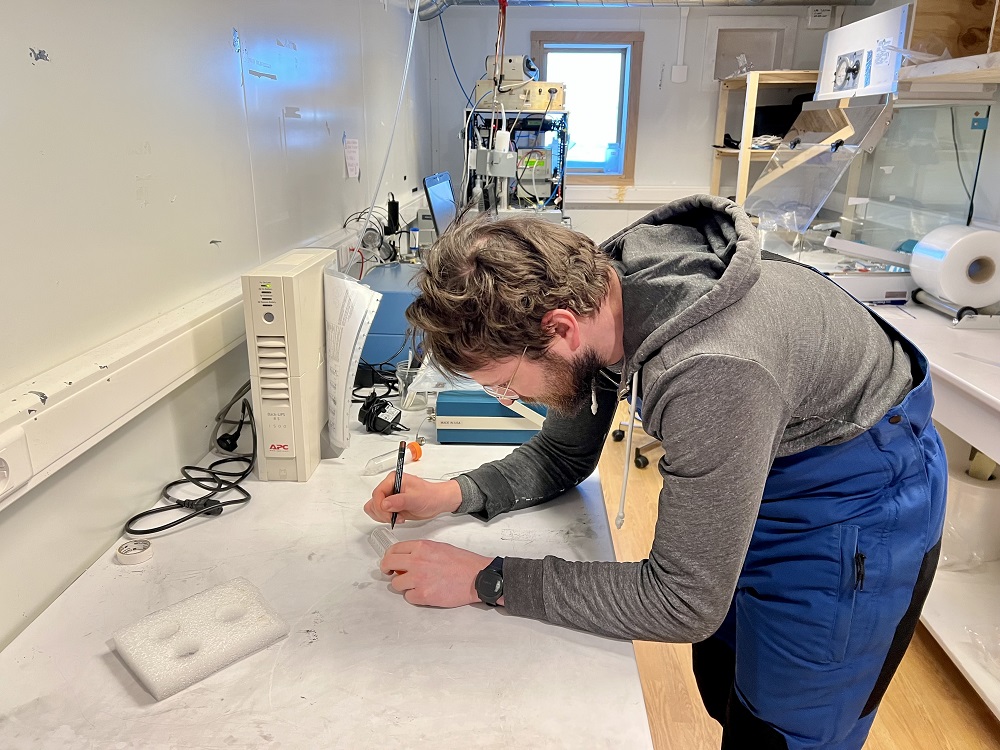

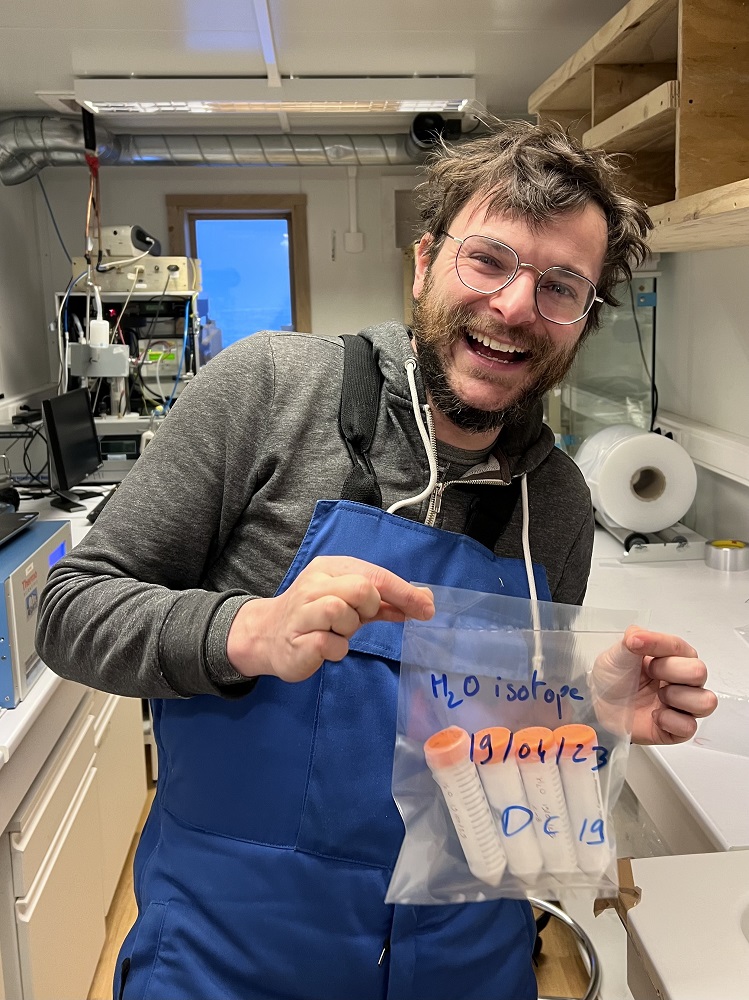

And behind that door is a long, icy corridor stacked with dozens of crates. These contain, in particular, Concordia’s « archives »: the reserves of ice cores taken during drilling operations to study our planet’s past climate.

Concordia was built on the site of the first « EPICA » deep drilling. Some of the fragments contained in these boxes are 740,000 years old!

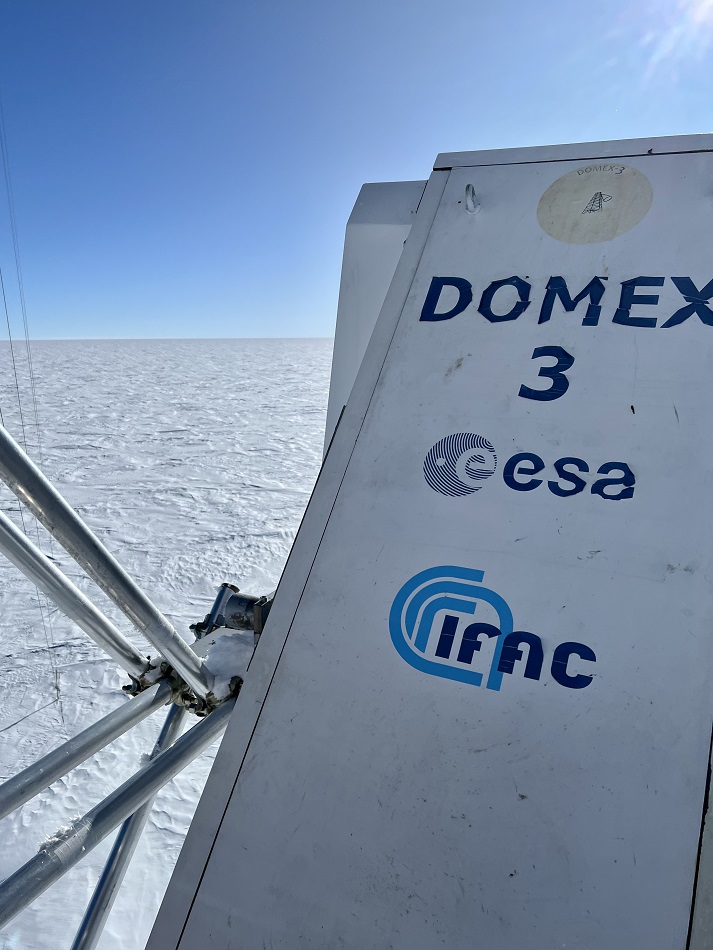

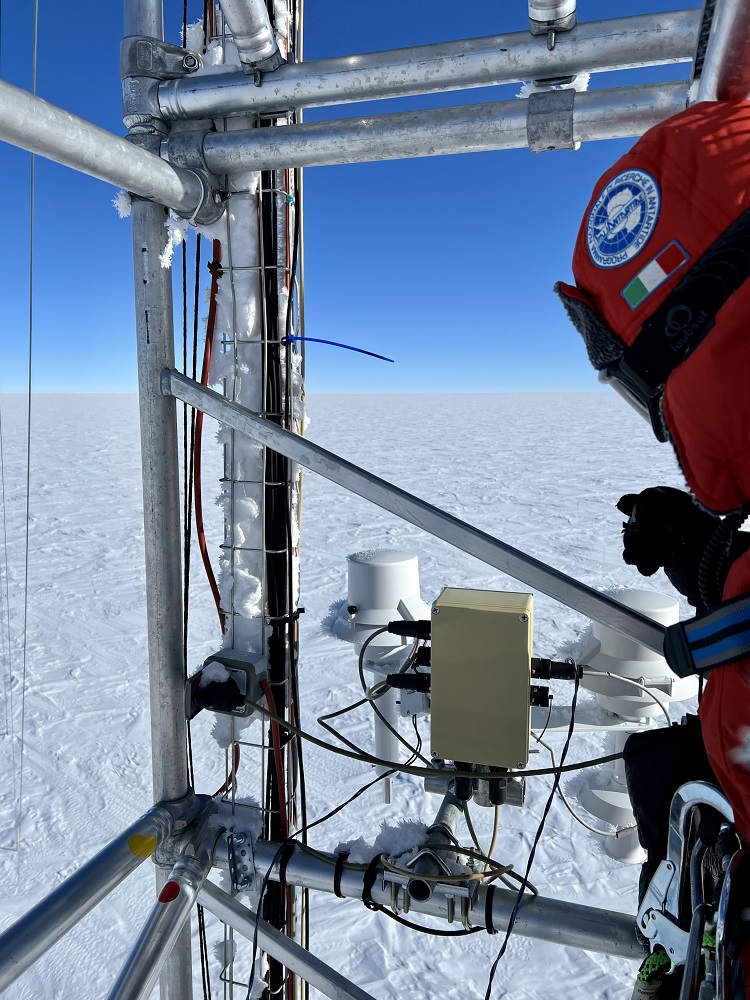

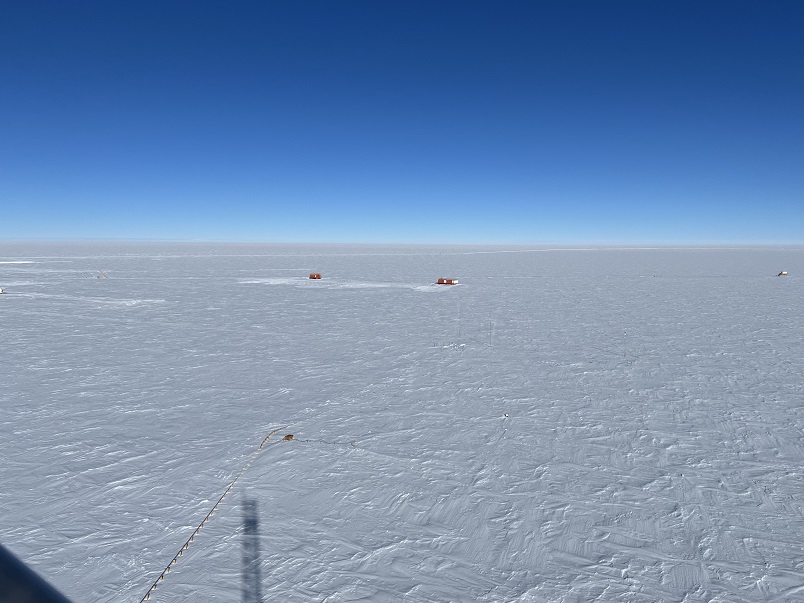

A new drilling has been underway for the past 3 years, at the « Little Dome C » site, 37 km from Concordia. This summer camp is in fact the site chosen for the « Beyond EPICA » project, the aim of which is to reach the oldest ice in the world: certainly more than 1 million years old and possibly 1.5 million!

These caves and crates are also the forerunners of another scientific project that is currently being developed at Concordia: the « Ice Memory » project, which aims to store samples of ice cores from the Arctic and glaciers around the world here, under cover, in order to preserve them for future generations.